March 26 and all that

Here's 3,000 words for American mega-site Alternet.org about UK Uncut, the tactical geniuses shot down by the Met's horrific, unapologetically political policing. The piece is an introduction to UK Uncut and the British protest 'movement' for Americans, and (among other things) a discussion of the potential power of networks versus hierarchies, after some of the reactionary nonsense spouted by Labour Party types after the protests and arrests on 26 March.

The flash mob, the 2000s’ post-ideological, apolitical updating of a situationist-style ‘happening’, was recuperated by capital with consummate ease, and co-opted into award-winning advertising campaigns. But now the flash mob is getting its own back in a massive way – repoliticized just like UK Uncut’s young participants, just like Britain’s gaudy, hyper-branded town centers.

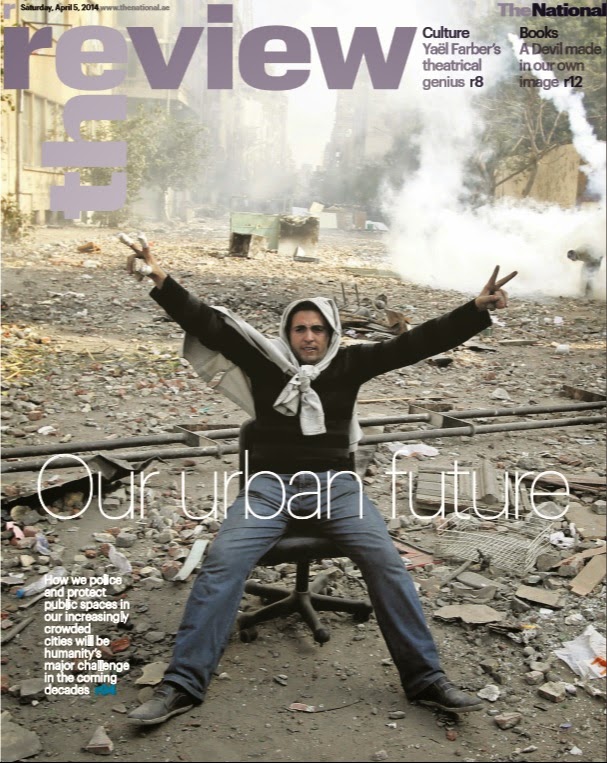

And here's a comment piece for The Guardian about the grotesque, strategic brutality of kettling, a bit of its history, and the effect it's had on a generation of young protesters.

It is often observed that kettling is designed to dissuade people from coming out to protest: if anything, it has the reverse effect on those who've experienced it. As protesters finally shuffled out of the Westminster Bridge kettle in single file, after seven hours imprisoned in freezing temperatures without food, water, toilets or freedom of movement, I saw several of them look the police in the eye – for that was all they could see, beneath a riot shield visor and a raised black snood – and say, some with humour, some with anger – but all with total defiance, "see you at the next one, mate".

Freshly radicalised by these experiences, it is little surprise that on 26 March, so many young people chose to reject the police-approved TUC march and masked up, seeking freedom and solidarity in the anonymity of the black bloc. I say this to the police: why should protesters engage on your terms, when these are your terms?

I'm writing a 10,000 word pamphlet for Random House about all this, out in the summer. Watch this space, and keep following the #demo2011 and #solidarity hashtags on Twitter.

.jpg)